Blog

1970s Inflation: Why Inflation Today is Nothing Like the 1970s

Inflation remains one of the very hottest topics today in the world of investing. It seems no review we are doing today is without some discussion of inflation and what is means for the viability of financial plans. Our plans typically don’t anticipate near double-digit inflation like we have seen especially in 2022. That’s a problem. Our view is that inflation will cool, but we do seem quite a ways away from the Fed’s target goal of +2%. What did they expect?!?!? Printing more money since 2018 than we have in the entire history of the United States! Yes, folks, eventually that will catch up with you and now we are having to bear the burden of unwinding all of this free money that was handed out to people in recent years.

With the government spending increasing, commodity prices surging, and money supply growth soaring, there is a damaging fear of a return to the 1970s kind of inflation.

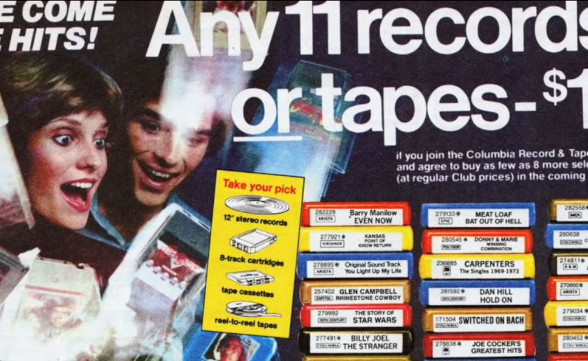

It wasn’t all frivolous back then. In fact, it was quite a tumultuous time, both economically and socially. The era saw crises from the Kent State shooting and the fall of Saigon to the Watergate and Nixon’s resignation and the Iranian hostage issue. In between, there was a deep recession, an economically crippling oil price increase and inflation was at its highest.

Today, prices, from groceries to gasoline, are spiking as the economy stumbles back from the global pandemic recession. The summer of 2022 saw nearly a 10% inflation rate, which was the highest in almost 40 years! And the memory of the awful economic time of the 1970s when the country was faced with double-digit inflation seems to strike a nerve, especially with investors.

So will we see a return to the 1970s-style inflation? History rhythms but it hardly ever exactly repeats. So we have to look very closely into this situation before us and use the 70s as a guidepost to managing through it, but let’s not get too enamored with the notion of an exact repeat!

What was Inflation Like in the 1970s?

Inflation in the 1970s was extremely higher than today. It accelerated over the decade and had a palpable, traumatic effect on economic policy.

Prices started creeping up in the mid-1960s due to the federal government’s heavy spending on the Great Society and the Vietnam War. From approximately 2% in the late 1060s, the great inflation rose to 12% in 1974 and 14.5% in 1980.

In retrospect, the underlying causes were:

- The country was hit with two oil shocks. During the 1973 oil embargo, the price per oil barrel quadrupled and doubled again in 1979 due to the Iranian Revolution.

- The Federal Reserve didn’t have the mandate to increase interest rates and slow down the economy to prevent inflation from rising until later when Paul Volcker was appointed as Federal Reserve chair in 1979.

The historic high inflation was blamed on exploding oil prices, greedy businesses, currency speculators and avaricious union leaders. But it’s clear that monetary policies that financed significant budget deficits supported by political leaders were the primary causes.

Carter referred to inflation as “the nation’s most pressing domestic problem.” Gerald Ford declared it “Public Enemy Number One.” And despite tough conversations from the White House, prices kept climbing.

Is History Repeating Itself?

The steady and lasting spike in prices seen during the past inflation created a time of disturbing and tremendous instability for Americans. And in light of the experience during the 1970s, the Déjà vu case for a protracted high inflation period is clear. Some similarities include:

- Supply disruptions caused by the pandemic recession and the recent supply shock leading to high energy prices by the Ukrainian war resemble oil shocks in the past.

- Increased government spending is causing strong demand amidst shortages of goods.

- Monetary policy is similarly, then and now, highly accommodative in the run-up to the shocks. After months of above-target inflation in advanced economies, a massive policy tightening might now be necessary to control inflation. This step might trigger a hard landing similar to the early 1980s.

Still, Volcker’s legacy is hovering over today’s decisions by Jerome Powel, the Fed’s current chair. “We’re strongly committed to using our tools to get inflation to come down,” he said recently, with many beads of sweat running down his brow. Yes, there’s a risk that increasing rates could trigger a recession. But “I wouldn’t agree that it’s the biggest economic risk. The bigger mistake would be to fail to restore price stability.” This sounds so much like old times. The real question we sit and ponder here is not the tough talk of the Fed and their ability to steer us to a soft landing, but just how much they can actually raise rates without really damaging the economy.

Reasons Why Inflation Has Returned

While the nation is freaking out by the potential repeat of historical times, experts believe there are three main factors driving the return of inflation:

- Structural factors: The deleveraging process in such a developed world has run its course, and we are in a period of structurally stronger demand creating structural underpinnings of a higher inflationary world. But this doesn’t mean it should be a period of runaway inflation; rather, the central banks should raise rates to align demand with supply.

- Economic overheating: The size and stimulus of the fiscal and monetary policy response issued during the pandemic recession were too large for the global economy to absorb hence the labor shortage. Fortunately, the central bank can manage cyclical demand by tightening monetary policy and demand falls.

- Supply issues: Most of these issues are clear such as the war in Ukraine and the shortage of semiconductors which have led to spikes in commodity and vehicle prices. While smart monetary policies can’t resolve these issues, people shouldn’t be too downbeat about it. The supply issues are likely temporary, and supply chains will normalize. Plus, central banks understand they shouldn’t use monetary policy to deal with temporary supply chain issues as it would likely plunge the economy into a severe recession.

Different eras, Different choices

While there are some similarities to the 1970s, and the Fed is seemingly choosing to let inflation rise today, there are critical differences between the economy (today and in the past) that suggest inflation is highly unlikely to return to that high level:

Demographics changes

The impact of demographic changes on the economy is defined by the ratio of young to middle-aged workers, which is considerably lower than in the 1970s. Demand for everything increased, adding pressure on inflation, and the ratio began to decline in the early 90s as older people transitioned to their saving years.

Today, the millennials have instead entered their spending years. Household formation is predictably increasing, and demand for goods and services is growing. However, until recently, this forecasted boost to growth from the millennials experienced low moments from the financial and pandemic crises. And while the ratio bottomed out in 2010 and is rising, it’s not likely to have a near similar impact as the 1970s. Consequently, while there might be a sustainable wave of demand going around, it’s not as huge as the one that hit the past.

Different labor market structures

In the past, workers had stronger bargaining power than today. Work unionization was higher, and strikes were more frequent and successful. The wages for union workers could keep pace with inflation, and even non-union workers routinely received cost-of-living increases.

Today, workers’ unionization is low, affecting the bargaining power of labor. Most states are considered “right to work” states, and political influence to boost wages is diminished. Besides, there are other structural changes affecting wage growth, such as global competition, the rise of the service sector, educational gaps and technological changes.

All these reasons limit wages from rising much for workers within the bottom half of the income distribution, ensuring the aggregate demand relative to supply is managed. This may change in the future, given the increased focus on income inequality, but today’s position is far from where things were in the 1970s.

Globalization changes

The US economy is still relatively closed, with only about 15% of products and services consumed coming from international markets. But that compares to just about 4% in the 1970s. Plus, the composition of imports is different. Despite all the discussion about re-shoring as well as the imposition of tariffs, most imports to the US are products with prices set in a far more competitive and open global market than in the past.

In conclusion: Lessons From the 1970’s Inflation

Eventually, clever monetary policy tightening in the past reduced inflation in major advanced economies and established the bank’s credibility, although at the cost of a deep recession. For example, the short-term interest rate in the US almost quadrupled between 1976 and 1981.

Today, in the near term, it’s likely that inflation will remain elevated as demand and supply shocks undergo the wage-and price-setting processes. But beyond the near term, inflation is forecasted to decline. However, the 1970s experience suggests some material risks to this outlook.

There are factors suggesting that inflation is likely to return to the target rate:

- Growth will slow as the central bank tightens monetary policy and global pandemic-related fiscal stimulus reduces. As the supply shocks caused by the Ukrainian war are priced, prices will stabilize. And as global logistics and production lines adjust, supply challenges will ease.

- After decades of developing credibility, inflation expectations will likely remain well-anchored.

- As long as various structural forces that depressed inflation prior to the pandemic persist, trend inflation will remain low.

However, there are some considerable risks that some of these three factors may not materialize as expected, and inflation will keep elevating. For example:

- Inflationary shocks could get more frequent or pronounced, causing repeated inflation elevations that may eventually de-anchor expectations.

- Central banks may remain accommodative and hesitant in their response. They could also fail to achieve their target so often that investors and economic agents eventually doubt their commitment or ability to manage price stability.

- The structural forces that controlled inflation over the years may fade.

This uncertain inflation outlook poses some policy challenges for the banks. However, it doesn’t require the central banks to deviate from the fundamentals that helped them develop credibility over the past decades. They should calibrate their policies keeping macroeconomic stability in mind, communicate their plans clearly and maintain credibility. The potential of a protracted high inflation period and a sharp spike in global interest rates has massive implications for emerging markets and developing economies.

As always, we will continue to adjust portfolios in response to major threats like inflation. We don’t want to try and out think the market too much, but rather, take a measured approach and wait for telltale signs that we should make changes, rather than getting too far in front of what we think will happen.